March: Remembering Trees

- Chloe Sparrow

- Mar 31, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 15, 2020

Recently I was talking with a friend, and she mentioned her child’s request for a treehouse at the bottom of their garden. She was surprised how enthusiastically I responded, I even surprised myself somewhat as I recounted the delights of my childhood treehouse. I’ve forever struggled to put into words what the treehouse of my youth meant to me, it was my first real experience of retreat and refuge in nature, and I really loved it. Time passed however and the treehouse was dismantled when the great Conifer tree’s were felled. It wasn’t personal, but it felt that way at the time.

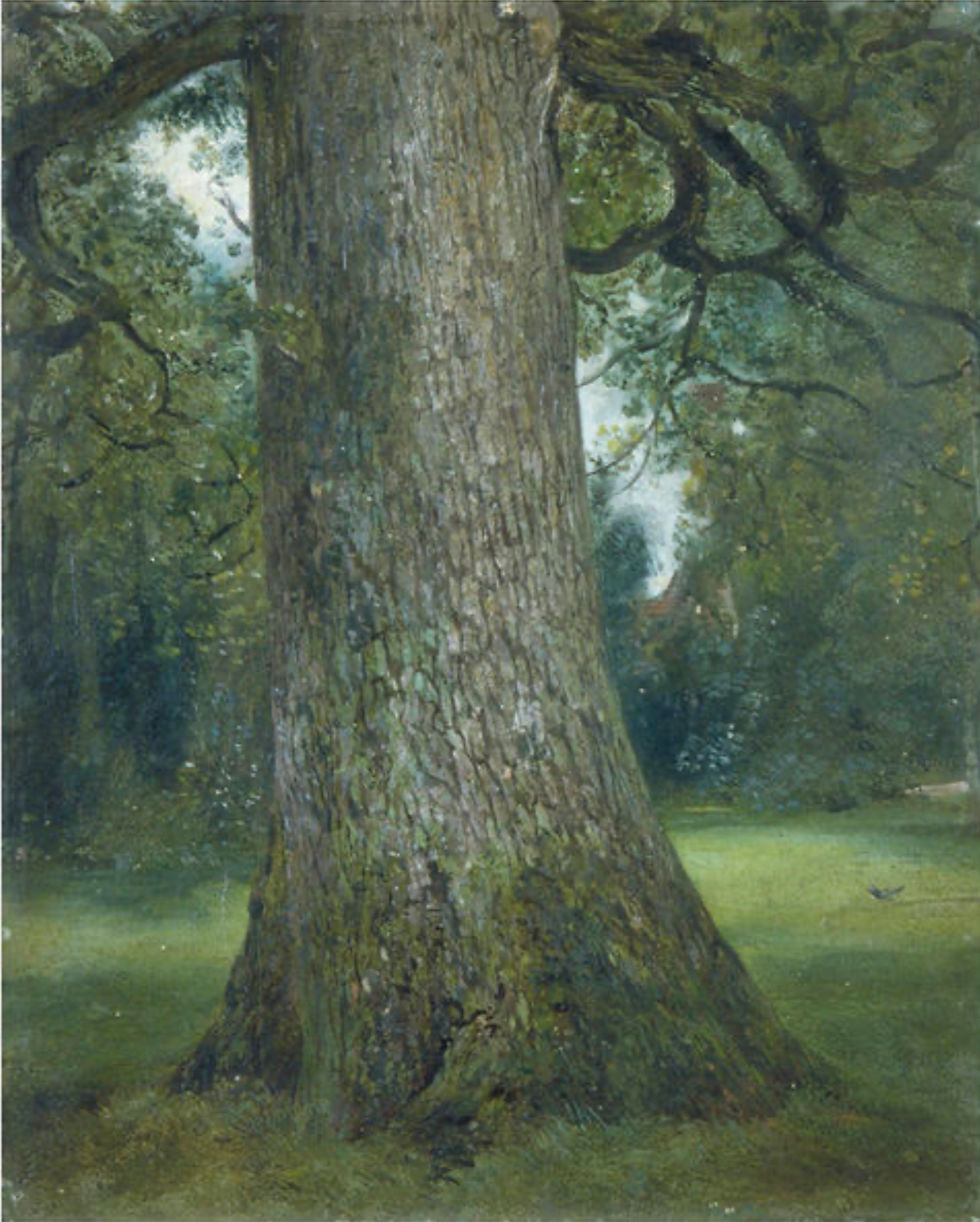

In the past I attempted to write about the old treehouse for my MA, in response to how our feelings about a place might impact on artmaking. I also tried writing about John Constables ‘Study of an Elm Tree’ which has always captivated me and reminds me of standing at the base of the treehouse. However both times I struggled with what I actually wanted to say. I struggled to acknowledge how much I missed the treehouse and the connection to nature it had provided me. Then, this March, owing to the Coronavirus outbreak I took the time to walk among familiar old trees, to stop and develop new relationships with them and found the opportunity to reflect on the past with a new found clarity.

You see, I was an imaginative child, growing up in a busy household meant I was often seeking privacy and let my vivid imagination take me elsewhere. I would frequently use my imagination to transform open spaces in my minds eye and the garden felt like a limitless canvas. It was often the place that I retreated to. It was also where I shared a den with my brothers. This consisted of precariously placed long planks of wood held up with who knows what, and which would re-erect itself in random places throughout the summer. Niggled by this, I presented my dad with a plan for a princess style castle, with moat, for prompt construction. While he suggested the plan was a little too ambitious, at some point a treehouse did begin to take shape, albeit not under my instruction. It was never particularly ‘finished’, or substantial in fact, being basically a small solid wooden platform nestled securely between two close tree trucks, but it was delightful. The two trunks I thought of as sisters, one a little bigger than the other, both independent but close, hugging perhaps. You had to climb up the more substantial trunk, aided by the branches of both trees, in order to get to the platform. It was a climb that soon became etched into memory, along with that glorious smell of the evergreen foliage and sap. Once on the platform the branches stretched over and above creating the perfect cocoon. I could voyeristically peer out and watch the coming and goings of home life without being disturbed. I had a great view of our semi-detached garden, and the neighbours too. It may have been my favourite place in all the world. And therefore its loss was a painful lesson in attachment, it definitely hurt. It’s an old wound now, but one that still makes it itself known from time to time, and I’ve come to question more recently whether the residual ache is more to do with unresolved anger than anything else.

With this in mind, I was reassured and comforted by the words of Ian Siddons Heginworth in his book ‘Environmental Arts Therapy and the Tree of Life’ in which he explores the fire behind anger that also has the power to purify old wounds. He writes about the Celtic Calendar in which the month of March is aligned with the Ash tree as a symbol of rebirth and new life. He focuses upon a mythic Ash tree called Ygdrassil, believed to represent the centre of the cosmos. According to mythology the Ygdrassil roots are connected to the underworld, they are the dark and raw material of our psyche, the ‘prima materia’ - or first matter, relating to the unconscious self, symbolising the past and that which we repress. This is the material that houses or stores our wounds, yet it is also the material from which we grow. Our ability to transform what is dark and painful into something knowing and beautiful, conscious and self-aware, is like our magic power, our act of alchemy. But as with any alchemy there must be a force that is applied, an energy, such as fire. It is appealing to me that the Ash tree can also be home to a very specific lead black fungus used in fire-making, as it is perfect for holding and nurturing sparks, and intriguingly named ‘King Alfred’s Cakes’.

The thing I’ve realised about burning, both literally and metaphorically, is the resulting ash - the rich fertile residue from which we can grow anew, free from the rage of the flame. The cyclic nature of fire, ash and growth fits perfectly with the coming of spring, in which we often search for a sense of renewal. When I think about spring and the outward force behind an actual spring during its release, I marvel at the formidable force and release of energy and I’m reminded of the power of anger, and the alchemy in transforming something dark into something valuable. It seems that having the courage to expose our shadows can empower us to move beyond them, which is something I witnessed recently with another friend when walking among the Redwood trees at Bute Park in South Wales at the beginning of the month.

It was a privilege to witness her be with her anger, rather than repressing its force, she found the courage to let the power in it spring forth. We did walking in the woods, hugging an almost furry Redwood tree, like children with a giant teddy bear. We realised that anger has its place and this seemed to set her pain on fire, allowing it to burn out safely, quickly even, purifying old wounds, leaving just ash. The experience of not denying anger felt transformative. It allowed for a shift in thinking, being and feeling. Walking with anger in nature nurtured our souls, allowing us both to spring forth a little lighter and brighter.

We all have wounds in our roots, wells of sadness that can rise to the surface when we least expect it. Letting ourselves feel anger doesn’t have to mean letting it consume us, but of course - as with any flame - we must take care and caution when processing it. Encouragingly, Ian Siddons Heginworth wrote “We cannot change our roots, they are all that we have to grow from, but we can transform the child’s pain into the adult’s power.” A welcome thought with so much uncertainty elsewhere, owing to the current Coronavirus pandemic. I wonder what we will harvest from the ashes of this crisis, once our everyday has been interrupted and all that we took for granted has been in review. We are having to face our vulnerabilities together now, despite the physical distance, and may we find refuge in nature and friends in the months to come.

Comments